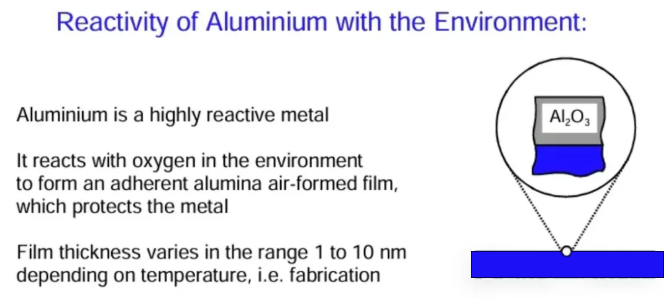

The effective use of aluminum is highly sensitive to its potential reactivity under various environmental conditions. Fortunately, in many cases, exposure of aluminum results in the rapid formation of an air-formed aluminum oxide film.

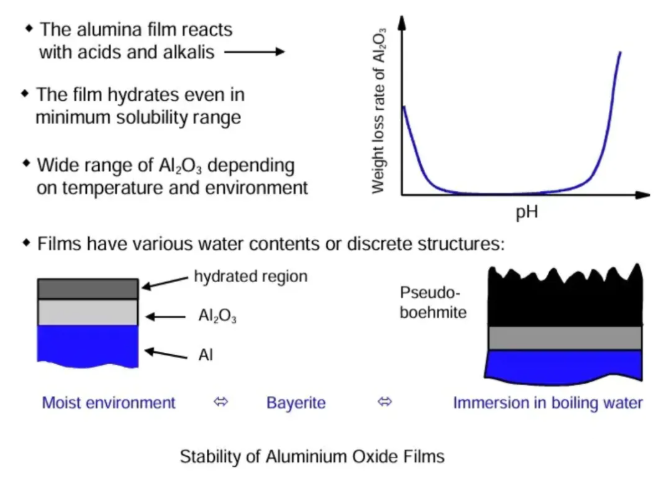

·At ambient temperature, the film is amorphous.

·Under geological conditions of 500 °C or above, both amorphous and crystalline aluminum oxide coexist.

·The amorphous film formed at room temperature has a limiting thickness of approximately 2.5 nm, which inhibits further oxidation of the substrate.

Depending on the specific conditions, the established potential may further react with the environment; therefore, hydration on the outer surface of the aluminum oxide film can continue to form multilayered films.

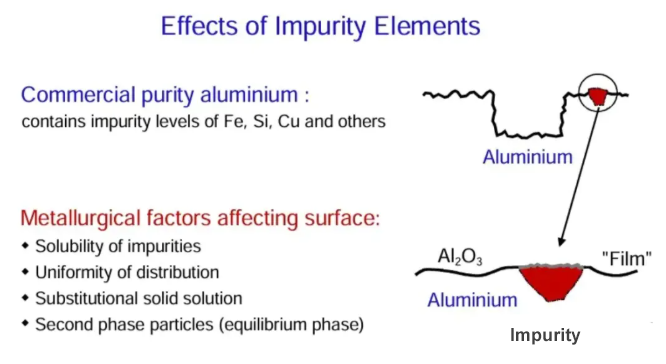

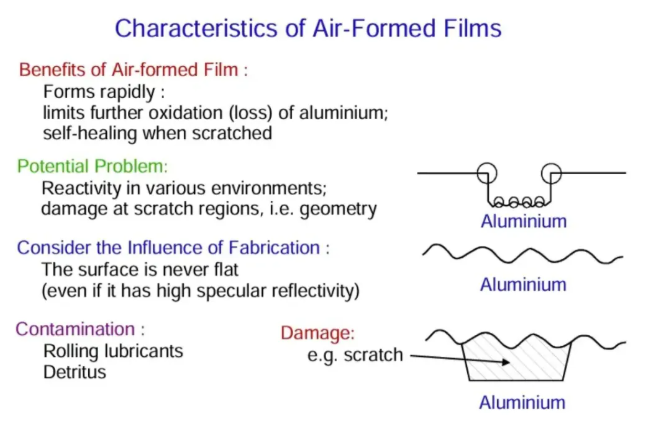

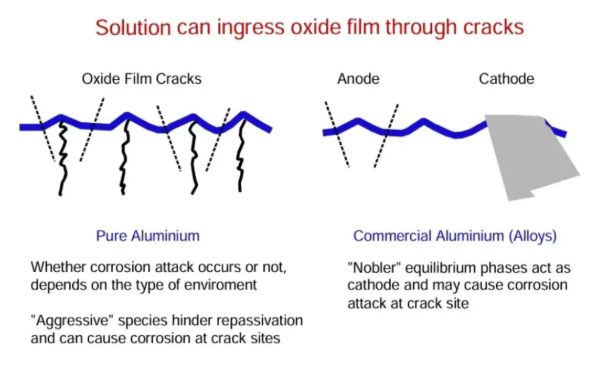

Aluminum’s high affinity for oxygen promotes the formation of the oxide film. It also ensures that similar films appear in substrate areas that are damaged or scratched. The figure illustrates some characteristics of the gas-formed oxide film.

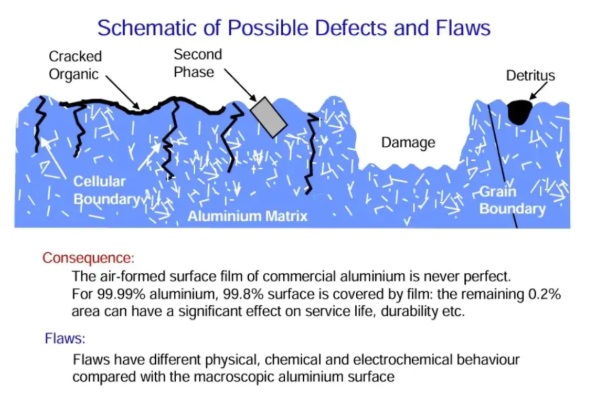

The gas-formed film on the aluminum surface contains various defects, generally referred to as flaws. Although the total area occupied by these defects is small, their formation process largely determines aluminum’s effective behavior.

Overview of the microstructure and surface properties of aluminum materials

·The atomic arrangement in aluminum’s unit cell is dense and face-centered.

·Within a given grain, unit cells are systematically arranged to provide the macroscopic material.

·For bulk materials, many different grains and their grain boundaries intersect with the material surface. These grains form during casting, deformation, and subsequent heat treatment.

·The material is composed of aluminum grains in different orientations, separated by grain boundaries.

·Above the grains, an air-formed film is distinctly present, forming a barrier between the external environment and the aluminum substrate.

·The macroscopic surface is relatively rough, with undulations resulting from specific manufacturing processes.

·Lubricants used during manufacturing may result in organic contamination on the surface.

·Impurities rolled into the surface provide additional areas for localized chemical changes.

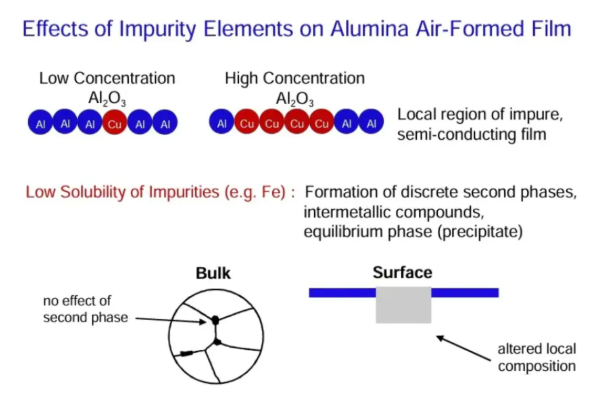

Alloying of aluminum may produce multiple effects:

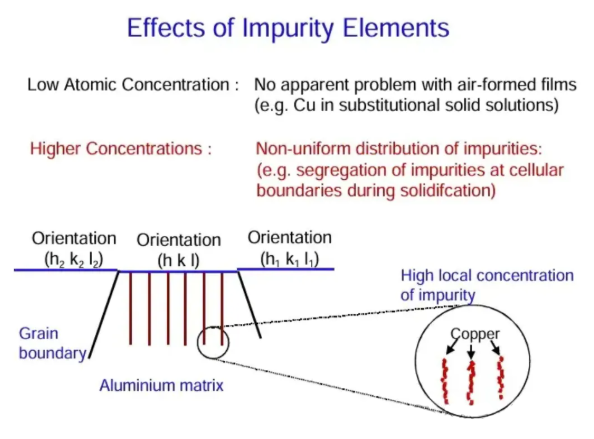

·Alloying elements may exist in substitutional solid solution within the aluminum matrix. However, once exceeding the primary solid solubility, a second phase or intermetallic compound may form.

·For age-hardenable alloys, finer intermediate phases may also precipitate.

·Common impurity elements in alloyed aluminum include copper, silicon, and iron.

·The solubility of iron in aluminum is very low. Therefore, in commercially pure materials, iron exists as a relatively coarse second-phase material.

The surface structure of aluminum alloys is far more complex than that of relatively simple pure aluminum. Various features that need to be considered are illustrated.

·Grain size, orientation and distribution.

·Alloying additions, precipitates, coarse equilibrium phases, intermetallic particles.

·Impurity segregation through casting and fabrication.

·Surface roughness through fabrication

·Surface stresses as a result of final fabrication processes

·Contamination with oils or other hydrocarbons.

·Incorporation of alloying elements into the air-formed film.

For pure materials in single-crystal form, the distribution of high-energy or potentially active surface sites is relatively clear. Therefore, in corrosion or metal dissolution, the loss of metal ions occurs preferentially at surface or step sites with curvature, rather than at low-energy terrace sites. However, for aluminum alloys that support their gas-formed film, any additional features particularly affect the activity of localized surface regions.

Essentially, aluminum corrosion is the process of aluminum reverting to an inorganic compound form. In low-pH or high-pH environments, and where the aluminum oxide film is reactive, the metal corrodes at a slow rate in a general or uniform manner.

For alloys, local heterogeneity in material morphology and composition leads to specific types of corrosion, such as intergranular corrosion and exfoliation corrosion, with dissolution extending to grain boundaries. In the presence of so-called aggressive anions (e.g., chloride ions), localized passive metal corrosion initiates at sites where the aluminum oxide film is ruptured and its repair is hindered.

Post time: Nov-29-2025